How Dogma Replaced Scripture and Led to Neoplatonism

Posted: April 7, 2018 Filed under: Church History, Heresy, Theology | Tags: council, creeds, dogma, dogmatics, Neoplatonism, Nicaea, Nicea Leave a comment

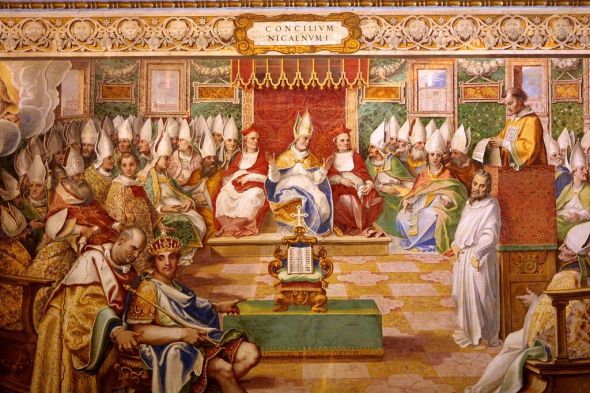

Council of Nicea Fresco in Capella Sistina, Vatican (Public Domain)

Excerpts from Anglican Canon Charles Gore, Dissertations on Subjects Connected with the Incarnation (London: John Murray, 1895), pages 171-2, 173.

The earlier mediaeval and scholastic method appears to put the dogmas of the Church in a wrong place. The dogmas are primarily intended as limits of ecclesiastical thought rather than as its premises: they are the hedge rather than the pasture-ground: they block us off from lines of error rather than edify us in the truth. By them we are warned that Christ is no inferior being but very God; and that He became at His Incarnation completely man, not in body only but in mind and spirit; . . . But thus warned off from cardinal errors, we are sent back to the New Testament, especially to the Gospels, to edify ourselves in the positive conception of what the Incarnation really meant. To Irenaeus, to Origen, to Athanasius, the New Testament is the real pasture-ground of the soul, and the function of the Church is conceived to be to keep men to it. But after a time there comes a change. The dogmas are used as the positive premises of thought. The truth about Christ’s person is formed deductively and logically from the dogmas whether decrees of councils or popes, or sayings of great fathers which are ranked as authoritative and the figure in the Gospels grows dim in the background. Particular texts from the Gospels which seem contrary to current ecclesiastical teaching are quoted and requoted, but though, taken together, they might have availed to restore a more historical image of the divine person incarnate, in fact they are taken one by one and explained away with an ingenuity which excites in equal degrees our admiration of the logical skill of the disputant and our sense of the lamentably low ebb at which the true and continuous interpretation of the Gospel documents obviously lies.

. . . .

. . . Greek philosophy was primarily concerned to conceive of God metaphysically. He was the One in opposition to the many objects of sense, and the Absolute and Unchangeable in opposition to the relative and mutable. In particular the divine immutability had a meaning assigned to it very different from that which belongs to it in the Bible, a meaning determined by contrast, not to the changeableness of human purpose, but to the very idea of motion which, as belonging to the material, was also supposed to be of the nature of the evil. There is no doubt that this Greek metaphysical conception of God influenced Christian theology largely and not only for good. In particular, through the medium of Neo-Platonism, it deeply coloured the thought of that remarkable and anonymous author who, writing about A.D. 500, passed himself off, probably without any intention to deceive, as Dionysius the Areopagite, the convert of St. Paul. With him the metaphysical conceptions of the transcendence, incomprehensibility, absolute unity and immutability of God are a master passion. In his general philosophy the result of his zeal for the One is to lead him to ascribe to the manifold life of the universe only a precarious reality. In his view of the Incarnation it produces at least a monophysite [sort of Unitarian or Monarchian] tendency.

Recent Comments