How Platonic Philosophy became Religion

Posted: January 1, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment

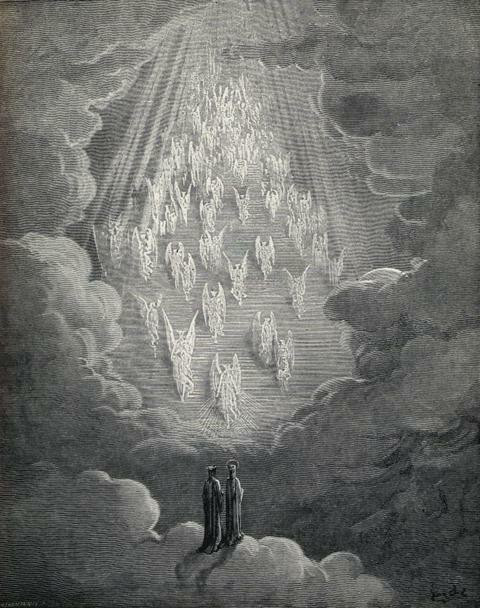

Public Domain

How Platonism in its search for ultimate truth and beauty evolved into Mysticism and Contemplative Prayer (Neoplatonism)

Excerpt from R. G. Bury, editor, The Symposium of Plato (Cambridge: W. Heffer and Sons, 1909), pp. xlviii-xlix, quoting Benjamin Jowett.

The philosopher is not only a student, he is also, by the necessity of his nature, a teacher. This is a point of much importance in the eyes of Plato, the Head of the Academy: philosophy must be cultivated in a school of philosophy.

The significance of Eros, as thus conceived, has been finely expressed by Jowett (Plato i. p. 532): “(Diotima) has taught him (Socr.) that love is another aspect of philosophy. The same want in the human soul which is satisfied in the vulgar by the procreation of children, may become the highest aspiration of intellectual desire. As the Christian might speak of hungering and thirsting after righteousness; or of divine loves under the figure of human (cp. Eph. v.32); as the mediaeval saint might speak of the ‘fruitio Dei’; as Dante saw all things contained in his love of Beatrice, so Plato would have us absorb all other loves and desires in the love of knowledge. Here is the beginning of Neoplatonism, or rather, perhaps, a proof (of which there are many) that the so-called mysticism of the East was not strange to the Greek of the fifth century before Christ. The first tumult of the affections was not wholly subdued; there were longings of a creature ‘moving about in worlds not realised,’ which no art could satisfy. To most men reason and passion appear to be antagonistic both in idea and fact. The union of the greatest comprehension of knowledge and the burning intensity of love is a contradiction in nature, which may have existed in a far-off primeval age in the mind of some Hebrew prophet or other Eastern sage, but has now become an imagination only. Yet this ‘passion of the reason’ is the theme of the Symposium of Plato.”

(d) Eros as Religion. We thus see how to “the prophetic temperament” passion becomes blended with reason, and cognition with emotion. We have seen also how this passion of the intellect is regarded as essentially expansive and propagative. We have next to notice more particularly the point already suggested in the words quoted from Jowett—how, namely, this blend of passion and reason is accompanied by the further quality of religious emotion and awe. We are already prepared for finding our theme pass definitely into the atmosphere of religion not only by the fact that the instructress is herself a religious person bearing a significant name, but also by the semi-divine origin and by the mediatorial role ascribed to Eros. When we come, then, to “the greater mysteries” we find the passion of the intellect passing into a still higher feeling of the kind described by the Psalmist as “thirst for God.” This change of atmosphere results from the new vision of the goal of Eros, no longer identified with any earthly object but with the celestial and divine Idea ([autokalon]). Thus the pursuit of beauty becomes in the truest sense a religious exercise, the efforts spent on beauty become genuine devotions, and the honours paid to beauty veritable oblations. By thus carrying up with her to the highest region of spiritual emotion both erotic passion and intellectual aspiration, Diotima justifies her character as a prophetess of the most high Zeus; while at the same time we find, in this theological passage of the Socratic [logoi], the doctrine necessary at once to balance and to correct the passages in the previous [logoi] which had magnified Eros as an object of religious worship, a great and beneficent deity.

This side of Diotima’s philosophising, which brings into full light what we may call as we please either the erotic aspect of religion or the religious aspect of Eros, might be illustrated abundantly both from the writers of romantic love-poetry and from the religious mystics.

(References follow to Edmund Spenser, Thomas Browne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Keats, among the romantic poets.)

Recent Comments